False friends: The ultimate giveaway of poor-quality translation

False friends: The ultimate giveaway of poor-quality translation

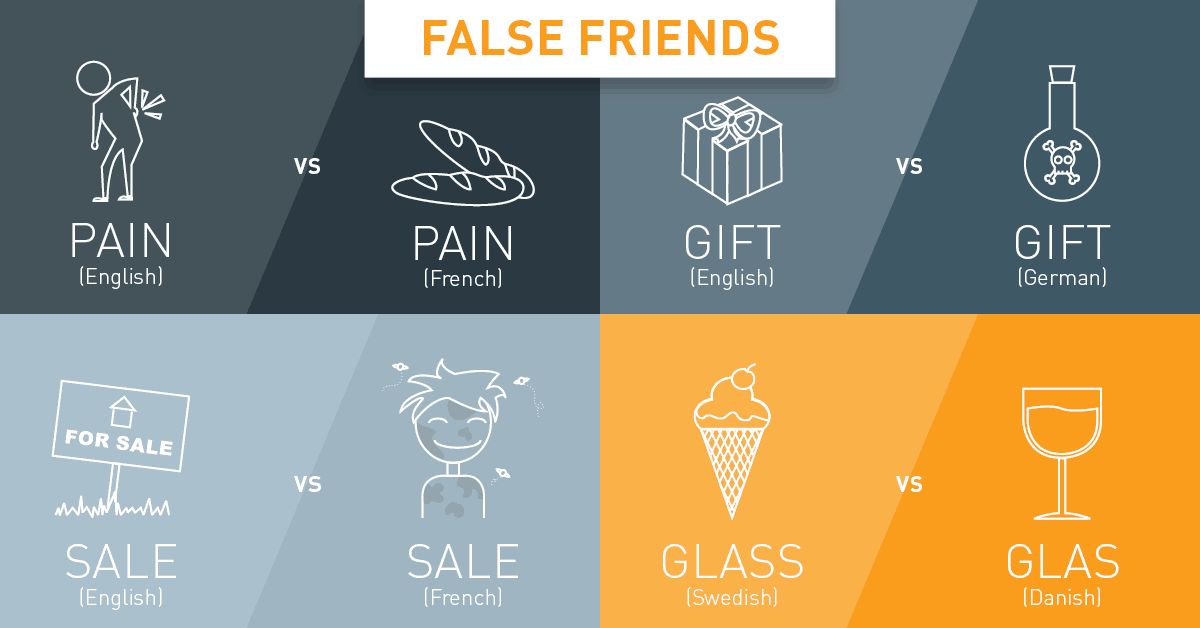

False friends are one of the clearest tells of a poor-quality translation. These misleading word pairs look similar across languages but carry very different meanings. They are the linguistic equivalent of a banana peel. They seem safe enough until you slip.

In everyday conversation, a false friend might cause a chuckle. In business, they can cost you money, damage your reputation, make your brand look ridiculous. And while they are easy traps for machine translation and amateur translators, they are entirely avoidable with professional oversight.

In this article, we unpack what false friends are, how they differ from calques, where they come from, why they are such a reliable indicator that your translation workflow is broken.

What are false friends?

False friends – also called deceptive cognates – are word pairs in different languages that look or sound similar but differ significantly in meaning. They are a well-documented phenomenon in contrastive linguistics. In psycholinguistics. In translation studies. In applied linguistics.

The term faux amis (false friends) was popularised by French linguists Maxime Koessler and Jules Derocquigny in 1928, but the concept continues to evolve. According to Kiršakmene (2023), false friends pose a particular challenge in cross-linguistic communication because they exploit surface similarity while concealing semantic divergence. This makes them especially problematic in machine translation. Especially problematic in non-expert human translation. Contextual interpretation is lacking in both cases.

Linguists generally distinguish three categories of false friends.

True false friends

These have a common etymological origin but diverged in meaning over time. For example, English actual and Spanish actual both derive from Latin actualis, but the English word means “real,” while the Spanish one means “current.”

Partial false friends

These share one meaning in common, but also have distinct, unrelated meanings in one or both languages. This creates context-sensitive traps. For example, French attendre can mean “to wait” but in certain contexts may be misread as “to attend.”

Accidental false friends

These are similar in form by coincidence, with no shared etymology. For instance, English gift and German Gift (which means “poison”).

The risk with false friends isn’t just semantic confusion. They often look correct to non-specialists. To machines. This creates plausible but misleading translations that are difficult to detect, especially when the rest of the sentence appears grammatically sound.

False friends can also carry pragmatic risks, as Kiršakmene notes. A term may not be technically wrong, but it may be inappropriate in register. In tone. In communicative intent. In formality level. This is where human translators – with subject-matter knowledge and cultural insight – outperform machines. Outperform non-experts.

The everyday false friends that fool most people

False friends show up all the time in casual conversation, web content, and marketing material – especially when translations are handled without linguistic oversight. Here are some common examples that even bilingual speakers can miss:

Term in English | False friend in target language | What the false friend means | Correct equivalent in target language |

Actually | Actualmente (Spanish) | Currently | En realidad |

Library | Librairie (French) | Bookstore | Bibliothèque |

Sensible | Sensible (French) | Sensitive | Raisonnable / Sensé |

Embarrassed | Embarazada (Spanish) | Pregnant | Avergonzado/a |

Fabric | Fábrica (Spanish) | Factory | Tejido / Tela |

Attend | Attendre (French) | To wait | Assister à |

Sympathetic | Sympathisch (German) | Likeable / nice | Mitfühlend |

Eventually | Eventualmente (Spanish) | Possibly / occasionally | Finalmente / A la larga |

Gift | Gift (German) | Poison | Geschenk |

Assist | Assistir (Portuguese) | To watch | Ajudar |

These mistranslations rarely trigger alarm bells during proofreading because they look “correct.” But to a native speaker or subject-matter expert, they stand out immediately. They undermine the credibility of your content.

False friends vs calques: understanding the difference

False friends and calques are often confused because they both lead to misleading translations. But the linguistic mechanisms behind them are different.

Not all misleading translations come from confusing similar-looking words. Sometimes, the issue is calquing – the direct, word-for-word transfer of structure or expression from one language into another. Unlike false friends, calques don’t usually involve vocabulary with misleading meanings. The words themselves might be correct, but the resulting phrase is unnatural, clumsy, or just not how people say things in the target language.

There are several types of calques.

Lexical calques

These translate fixed phrases too literally. For example, “Terms and Conditions” is often rendered as “Términos y condiciones” in Spanish – a direct mirror of the English.

It might look acceptable at first glance, but in legal or user-facing contexts, native Spanish websites overwhelmingly prefer “Condiciones de uso” or “Condiciones del servicio”. This is a textbook lexical calque: technically accurate, but contextually wrong.

Structural calques

These happen when the syntax or grammatical construction of a source-language expression is imposed directly onto the target language, creating a phrase that’s technically understandable but unidiomatic.

For example, in French, a direct calque of “make a payment” might result in “faire un paiement.” While grammatically acceptable, it sounds mechanical or foreign. A native French speaker would more naturally say “effectuer un paiement” or “régler une somme” depending on the register.

Semantic calques

This type of calque happens when an existing word in the target language adopts a new meaning under the influence of a foreign language. The word itself already exists. It just gets used in a new, borrowed way that doesn’t align with native usage.

A good example is in German, where the verb realisieren has started to be used more and more like the English “to realise” (as in “I just realised something”), due to English influence.

German calqued usage: Ich habe realisiert, dass es zu spät ist. (I realised it was too late.)

Natural German usage: Mir ist klar geworden, dass es zu spät ist.

Originally, realisieren in German meant “to make real” or “to carry out” (e.g. ein Projekt realisieren = “to execute a project”). The newer “mental realisation” meaning is a semantic calque from English, and while increasingly common, it’s still considered non-idiomatic or awkward in formal writing.

The danger with calques is subtlety. They don’t usually trip alarms in spellcheckers or QA tools. But for a native reader, they undermine the credibility of the content. They’re often a red flag that the translation was handled by someone translating too closely to the source. Or worse, by a machine.

What false friends and calques reveal about translation quality

When a translation contains a false friend or a calque, it is rarely just an innocent mistake. It is a signal that something is wrong with the process behind the text.

It suggests that the translator may not have subject-matter expertise. The work was likely done with minimal revision. Or no revision. Machine translation may have been used without proper post-editing. The project was rushed. Underpriced. Handled without sufficient oversight.

This has real consequences. In fields like legal, medical, technical, financial content, even one misleading word can confuse users. Can affect compliance. Can invalidate contracts. Can trigger legal action. In marketing, it can dull your messaging or make your brand sound untrustworthy. And when mistakes force retranslation or legal clarification, the costs of poor quality quickly outweigh any initial savings.

For buyers, these issues are often visible even without knowing the language. False friends leave traces. Calques leave traces. They look correct at first glance but feel off once you pay attention. If you spot one, there are probably others.

They offer a quick test. Was this text translated by a professional who understood the brief? Who understood the brand? Who understood the context? Who understood the audience? Or was it pushed through a machine and tidied up after?

In short, these mistakes are not just linguistic errors. They are clues about the quality of the entire translation workflow.

Why machine translation falls into the false-friend and calque trap

Machine translation systems have come a long way. But when it comes to nuance, they still get it wrong. False friends and calques are some of the most persistent errors. Here’s why.

Pattern replication, understanding absent

MT models (including neural and LLM-based systems) do not understand meaning the way humans do. They work by predicting the most likely word or phrase based on patterns learned during training. If a false friend or calque shows up often in the data, the system will keep reproducing it. Even when it’s wrong in context.

Ambiguity triggers the wrong guess

When a word has multiple meanings or when the source sentence is ambiguous, MT systems tend to go with the most common or familiar translation. They don’t pause to ask: “What’s the intent here?” This leads to surface-level translations that miss the point.

Structural mimicry

MT often mirrors the structure of the source language too closely. Instead of adapting grammar to sound natural in the target language, it sticks to the original blueprint. Instead of adapting phrasing to sound natural, it copies. That’s how structural calques happen. Phrases that are technically correct but completely off in tone or fluency.

Gaps in training data

MT works best for high-resource languages like English, Spanish, French. But in many languages, or in niche domains like legal or medical content, there isn’t enough high-quality training data. As a result, the system falls back on generic or literal translations, where false friends thrive. Where calques thrive.

No internal alarm bells

False friends often “look right,” so the machine has no reason to doubt them. Calques often “look right.” There’s no built-in mechanism to flag: “This is technically accurate but sounds wrong.” Without human review, these errors slip through unnoticed.

What this means for buyers

When you see a literal, grammatically correct translation that still feels off, chances are MT is at fault. It lacks the ability to interpret subtle meaning, adjust syntax, consult the right equivalent grounded in subject-matter context. In cultural context. At best, it is recycling shallow patterns. At worst, it is acting as a false friend factory.

MT remains powerful for quick, internal drafts. But for anything public facing – legal pages, instructions, marketing – you need professional translation systems. You need workflows to spot these invisible failures before they impact your brand or compliance.

False friend fail: the pen that gets you pregnant

One of the most famous examples of a false friend gone wrong comes from Parker Pen. The brand meant to reassure customers with the slogan: “It won’t leak in your pocket and embarrass you.” But in Spanish, this was reportedly translated as:

“No se filtrará en tu bolsillo y te embarazará.”

The problem? Embarazar does not mean “to embarrass.” It means “to impregnate.” What was meant to be a product reassurance turned into an absurd claim that the pen might get someone pregnant.

This story has been widely shared, but its original source is Blunders in International Business by David A. Ricks (1974), where the author thanks Parker Pen’s management for candidly discussing the incident and the cause behind it. Ricks attributes the error to correspondence with the company, suggesting it was a real blunder.

To complicate matters, the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) does list one archaic meaning of embarazado as “embarrassed” (DLE, RAE). But in practice, no native speaker would use it this way. That is the key point: no fluent Spanish speaker or professional reviewer would have let this pass. It is the kind of mistake that only happens when no qualified human has been involved in quality control.

False friends like this are not just linguistic slip-ups. They are clear signs of poor-quality translation. They undermine trust in a brand faster than almost anything else. When translation is handled properly, these mistakes do not happen.

How professional translators avoid these traps

False friends and calques are unlikely to slip through when a translation is handled by professionals. That is because expert translators do more than transfer words from one language to another. They interpret meaning, context, intent. They reshape the message so it feels natural to the target audience.

Here is how professionals get it right.

Subject-matter expertise

Professional translators who specialise in legal, medical, technical content understand both the terminology and how it is used in practice. They know when a term may look right but carry the wrong meaning.

Glossaries and style guides

Well-defined linguistic resources such as glossaries and style guides ensure consistent tone. Consistent terminology. Consistent phrasing. These are usually developed in partnership with the client. Updated as projects evolve.

Translation memory and QA tools

Technology supports the process by highlighting inconsistencies. By flagging potential errors. But decisions are always made by the human translator.

Human revision

A second linguist reviews the translation to catch awkward phrasing, false friends, source-language interference. This extra step is key to ensuring the final version reads smoothly.

Contextual research

Good translators check how similar content is written in the target language. They refer to real websites. Regulatory sources. Market-specific materials. Industry publications. All to guide their choices.

In short, professional translation is a deliberate process. It ensures that content not only avoids mistakes but also sounds correct to native readers. Sounds credible to native readers.

Bad translation has a tell

False friends are not just awkward. They are revealing. When you see one in translated content, it tells you something important: that the translation was not properly checked. Or worse, was never truly localised in the first place. It shows that the brand did not invest in quality. Did not invest in context. Did not invest in native-language credibility.

Whether it is a calqued legal heading or a marketing slogan gone viral for the wrong reasons, these mistakes signal amateur work. They are the kind of errors that undermine trust. That stick in a reader’s mind for all the wrong reasons.

If your content matters, your translation process needs to be airtight. That means specialist translators. Proper review. Systems designed to avoid the pitfalls of literal translation. Because in language, looking right is not the same as being right.

Need help avoiding these traps? Talk to us about building a better, smarter translation workflow.